Since I was in middle school, I have heard a drum beat of the need for American schoolchildren to spend more time in school and on homework to catch up to our international peers.

This is true today as well. I’ve seen some gut-wrenching articles about ditching summer vacation, and even the President has opined on extending the school day and year.

My narrow, empirical data tells me that we have been extending the school day for decades and we have not seen any results. This belief has led me to expound to anyone I think will be receptive to the idea that:

“If someone were to make a chart showing time in school versus achievement, I bet there would be a negative correlation.”

Just recently, a colleague Carlos Jerez Hanckes (@cfjerez) replied, “And you should be the one to make that chart.”

Challenge Accepted. But first, a warning

Disclaimer: What follows is a very cursory analysis of some data I munged in an afternoon. This is not a scholarly work, and I am not a scholar of education. In fact it could be rife with confirmation bias

With that out of the way, we can begin.

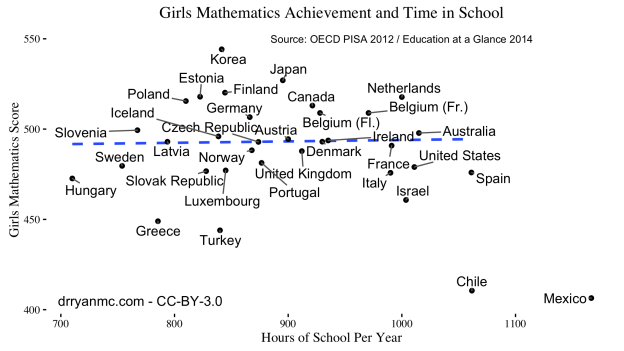

First, I looked for historical data for school attendance and length of school year. I did find data from the National Center for Education Statistics for select years going back to the 1800s.

As the figure shows, the number of days in the school year has increased throughout the 20th century, and had a small bump in the late 1990s. Nevertheless, there is not reliable data on student performance that I could find going back before the late 1980s. Ideally, I would find data that showed the impact of the entire range of school year lengths, but it was not to be.

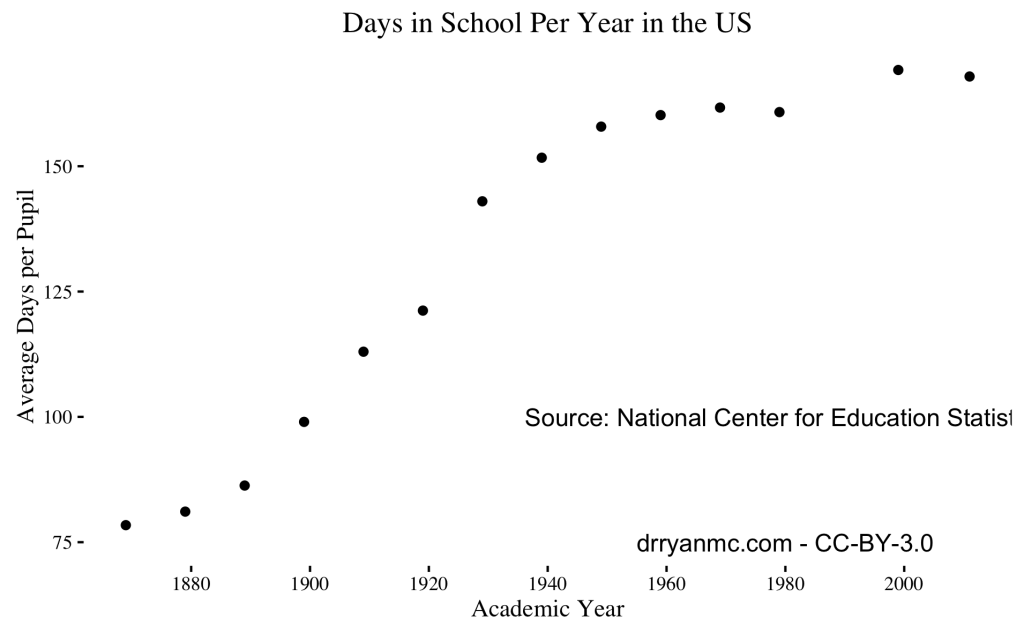

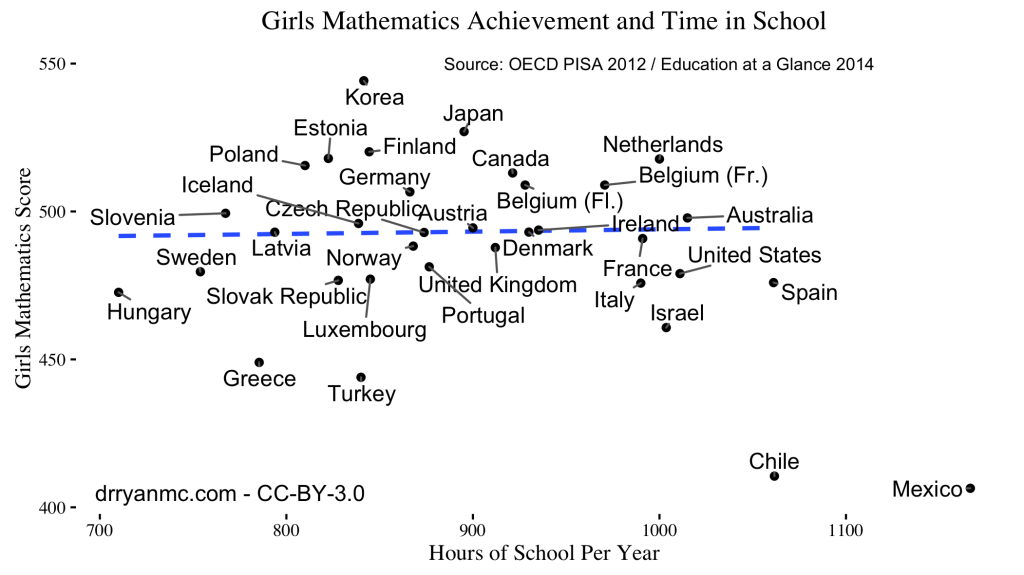

However, the OECD does have data for its member countries (comme on dit first-world countries), and some others, that has length of the school year in hours, and achievement on an international test. This is the Programme for International Student Assessment’s (PISA). While many are not keen on testing being the best metric of student ability, in this case it is about all we have. Additionally, the OECD has data on the time spent on homework per week in their Education at a Glance report.

Now necessarily these data sets are not at the exact same snapshot in time, nor are they easy to merge. For example, one table has England and Scotland different while the other has just Great Britain. There was no data for School Year for Scotland so I deleted that and used United Kingdom to refer to England (where most of the population is). Also, Belgium has two different lengths of school year for the Flemish and French regions, but only one PISA score. I used the PISA score for both of these.

And the results are here:

I’m showing the results for Girls scores in mathematics, because 1) a majority of my children are girls, and 2) I didn’t want to simply average the genders, and 3) I am a STEM educator and am interested in preparation for college in quantitative reasoning. Also, the students taking the exam are 15 and the school length is for 13 year-olds, so, as I mentioned they don’t line up perfectly.

The result is that there is no statistically significant relationship between hours in school per year and performance by students. The dashed line on the plot is the line of best fit when Mexico and Chile are removed. If I left those two countries in, there is a significant negative relationship between the two variables.

This result is not saying keep kids out of school to make them smarter. What it says to me is “Don’t tell me that kids need more time in school to perform better.” Clearly, there is something going on to make the higher-scoring countries get there that is not time in school.

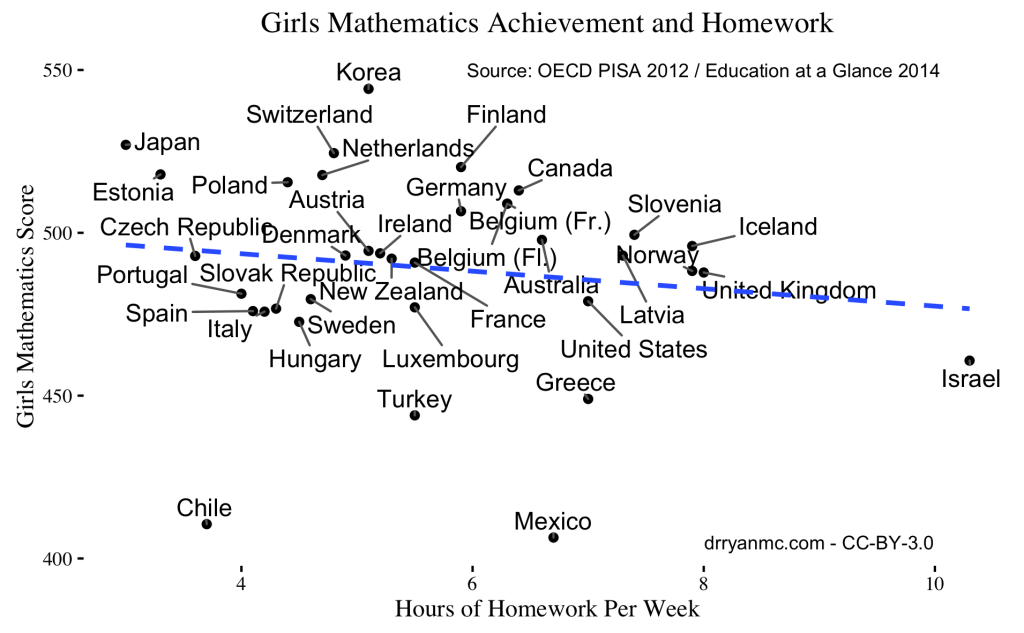

Maybe, the achievement is due to more homework assignments. Nope:

Other than indicating that I’m glad I didn’t have the amount of homework that an Israeli pupil has, this chart indicates that more homework does not make a better student. I know this chart looks at different data, but can we stop have kindergarteners have homework and let them be kids.

As my disclaimer above noted, there is likely more to the story than these few indicators. Of course, there is more to good education than more time in school and more homework assignments also.

A somewhat related recent TED talk:

https://www.ted.com/talks/sal_khan_let_s_teach_for_mastery_not_test_scores?language=en?utm_source=tedcomshare&utm_medium=referral&utm_campaign=tedspread